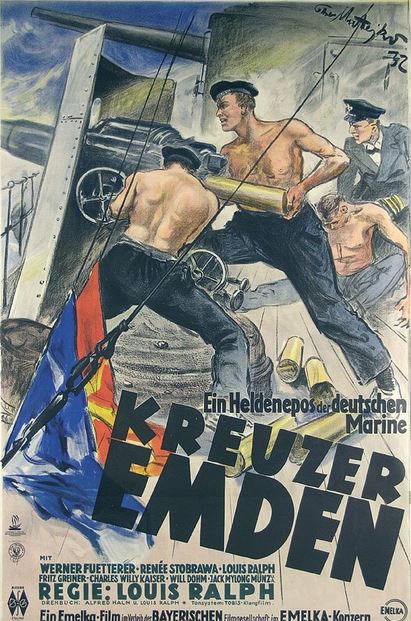

On the night of 22nd September 1914, a lone German cruiser slipped unnoticed into the waters off Chennai. Once the ship was in range, its commander Karl von Müller gave his crew the order to attack the city. The powerful beam of a lighthouse revealed a potential target: three fuel tanks belonging to the Burma Oil Company. For half an hour, the German gunners bombarded over 130 shells at the city, first setting the tanks ablaze and then firing at the High Court, the Port Trust and other prominent city buildings. A merchant ship went down in the harbour, killing five sailors. By the time the British guns retaliated, the SMS Emden had sailed away. It left behind a fearful, devastated city. Thousands tried to flee, fearing another raid; prices of commodities shot up, and trade was paralysed. The damage to the economy was estimated at a million pounds,

notes Srabani Basu.

The memory of the Emden raid has survived in the city's folklore, and in its vocabulary as well. In colloquial Tamil, an

emden or

amdan is a person who acts with audacious daring - unafraid to take on anyone, whatever the odds. A quick search on the Internet shows that

emden is defined variously as 'a daring and capable person', 'a particularly cunning person' or 'manipulative and crafty'. Parallel Tamil terms are cited -

jithan,

eththan,

killadi (which I presume is slang derived from the Hindi

khiladi). The word collocates frequently with

periya (big) in phrases used to disparage smart alecks and blowhards:

In chennai if someone behaves arrogantly we ask them do you think you are emden or what? (Nee enna periya emden aa?) (Indian Defence)

Emden was a famous ship during the war time.... there is still a cliche in TN wen someone does something big unexpected or is kinda adamant, they say 'periya emden thaan ivan'!! (Balaji's Thots)

In the thirties and forties the word ‘Emden’ was a metaphor (in Madras) for someone thought to be super-clever and go-getter. “Avan periya Emden-da” (is he the Big Emden?) was the expression heard in Madras lot of times. (The Intuitive Traveller)

This appears to be the more common usage of the word. Here and there,

emden has been defined as someone who is tough, strong and unbendable. A

Hindu article

on Tamil slang derived from colonial-era expressions provides the meaning 'strict, authoritative' and adds this note:

This is usually used to describe someone very strict by nature; boys call the strict elder of the village ‘Emden’ and describe his arrival to a place as ‘Emden vanduttan’. Emden is actually the name of a German ship that bombarded Madras in 1914 and created a lot of panic. One of actor Bharath’s films was originally titled Emden Magan (later changed to Em Magan) to denote a strict father.

Chennai city historian S Muthiah, who is also an amateur lexicographer includes

emden in his guide to

Words in Indian English, where it is defined flatly as 'a brave man'. The word is also found in

Sinhala and in Malayalam, where a variant,

yemandan, is an adjective meaning 'unusually huge and/or powerful' according to

this article on Malayalam slang.

Even today people in North Kerala call dark stout guys ‘Yumunden’ without knowing that the origin of the name was the hulking WW1 German frigate SMS Emden. (Maddy's Ramblings)

Curiously enough, the Tamil usage of 'periya Emden' is echoed in an Australian catchphrase. After a round of daring exploits in the Indian Ocean, the Emden was finally brought down by the Australian cruiser

Sydney at Cocos Islands in 1914. The victory was much celebrated in Australian films of the time and gave birth to this expression about colossal conceit, noted by Eric Partridge in his

Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English:

didn't you sink the 'Emden'? An Aus. army c.p.(1915-18) contemptuous of arrogance or too good a 'press'.